If anything captures the imagination, it is the Tour de France. Almost everyone of my generation (Sander, 1984) was captivated by cycling because of 'the Tour'. I could watch mountain stages for hours, preferably from start to finish. Ringing names like Glandon, Iseran, Galibier. I could really dream them up. Many of my contemporaries in their 20s spent all their summer holidays ticking off those very climbs, those of the Tour. We have listed the best of them. Just because it's fun. And to inspire your next cycling holiday in France.

Alpe d'Huez

This is perhaps the most famous mountain from the Tour. It is also the Dutch mountain, with the famous turn 7 for the Dutch. The 21 hairpin bends are an inspiration for many cycling brands. It's also always nice for TV and while not the prettiest and not the toughest, the 9% is pretty hefty on average. There are so many stories on the flanks of this col. That's almost enough for a separate article.

Every year, many Dutch and Belgian people go camping in Bourg d'Oisans at the foot of the Alp. The 21 hairpin bends are an unforgettable cycling experience that cyclists definitely want to have experienced. For the real connoisseurs: there is also a 'back' that you can climb, but it is less popular due to the lack of hairpin bends and therefore the lack of heroics.

Read also: Riding the dream: biking out a day ahead of the peloton on the Alpe d'Huez

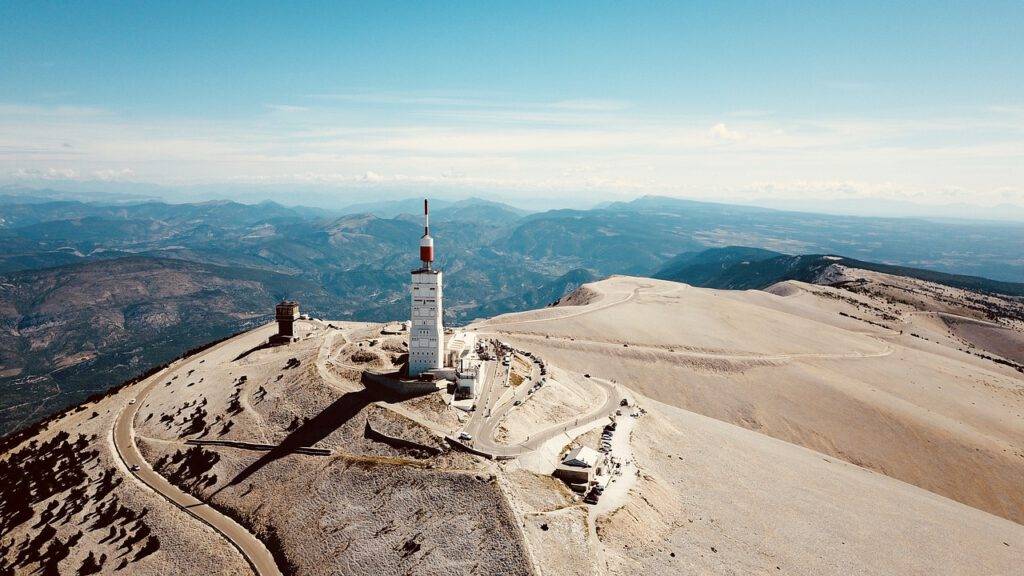

Mont Ventoux

With a nickname like 'the giant of Provence', Mont Ventoux no longer needs to prove itself. 15 times the Tour de France passed over Mont Ventoux, 9 times the finish of a tour stage was at the top of the bare mountain. The Tour de France has a crazy preference for the approach to the summit via Bedoin (14 times), while the climb from Malaucene is at least as tough! Perhaps a tip for the tour management!

Col d'Aubisque

Like the Tourmalet, the Aubisque is a true classic Pyrenean giant. As many as 48 times it has been climbed during the Tour de France, the first time it was climbed in 1910. François Lafourcade was the first rider to pass the summit of the Col d'Aubisque on a bicycle during the Tour de France. Later, not only would thousands of professional cyclists follow him, but millions of amateur cyclists also made the effort to cycle to the summit. The climb itself is not too tough, but mostly very long.

Col du Télégraphe

The north face of the Col du Télégraphe is siamese twins with the Galibier. This climb is often seen as part of the (higher) Galibier. It usually does not count for the bulbous jersey. Of the more than 30 times the mountain was in the Tour de France, it only counted for points 18 times. But if you have to cycle up it, it's still steep!

Col du Galibier

The Galibier is rightly a Classic Ride! It was the favourite climb of the inventor of the Tour de France, Henri Desgrange. There is a monument to his memory on the south face of the birch. In 2011, the stage finish was on the Col du Galibier. Andy Schleck won this memorable stage after a 60-kilometre solo that marked the highest finish ever in the Tour de France!

Col de la Madeleine

The Col de la Madeleine, well-known from the Tour de France, connects two Alpine valleys and is often the race's sharpest enemy. This mountain pass, which has formed a stage 24 times since 1969, with the last time in 2013, is characterised by its challenging climb. Thierry Claveyrolat, for example, soloed to victory here on a hot day in 1990. Although the Madeleine officially falls just short of 2000 metres, there is a sign at the summit that reads '2000m'. A mistake, as the pass measures 1993 metres. Climbing this col is a real challenge; the steepest kilometre has a gradient of 11%, and the longest route from Feissons-sur-Isère counts more than 20 kilometres with an average percentage of 6.2%. So think carefully before embarking on this hellish ride!

Col de la Colombière

In the Tour de France, this climb is often used as a transition pass. The last kilometre is ideal for attacking to start the descent with a lead. Although this climb is not enormously high, it is technically difficult. In particular, the north face of the climb, from Scionzier is a running climb that gradually gets steeper and steeper. The devil of this climb is therefore in the last 5 kilometres where the average percentages do not go below 9%. At over 10%, the last kilometre is the steepest part, so it is important to classify this climb properly.

Read also: Col de la Colombiere

Col de Peyresourde

Climbing the Peyresourde is a real challenge in the Tour de France. This climb in the Pyrenees has featured in the Tour book 45 times, with a first edition in 1947. Particularly memorable was the 10th stage in 1998, where Rodolfo Massi, also known as the 'Apothecary', had great influence and seventeen riders failed to reach the finish. Despite being considered a first category climb, due to its relatively limited height and gradient, the Peyresourde still offers a serious challenge. You can tackle this climb from two sides: a short climb from Armenteule of 8 kilometres with a gradient of 7.6% and a longer route from Bagnères-de-Luchon of 15 kilometres with a gradient of 6.1%. Both sides are feasible for a trained cyclist and they offer a pleasant climbing experience without extremely steep segments. Ideal for climbing enthusiasts not looking for huge gradients.

Col de Peyresourde, Armenteule, France

- Distance: 8.3 km, Elevation gain: 610 m, Average grade: 7.2 %

Col d'Aspin

In the 1950 Tour de France, there was quite some consternation on this pass during the stages from Pau to Saint-Gaudens. The French supporters who had gathered on the climb were rather wanton towards foreign riders. The Italian riders in particular suffered, stones and bottles were thrown towards them and the road was obstructed. Consequently, at the end of the stage, the entire Italian team boarded the train home, thus the Tour de France lost one of its great contenders that year, Gino Bartali. In total, the Tour de France caravan has crossed the Aspin over 70 times over the years, making it one of the most climbed passes in the Tour. The Col d'Aspin is of course famous for the legend of Eugène Christophe's front fork.

Col d' Aspin, Arreau, France

- Distance: 11.6 km, Elevation gain: 749 m, Average grade: 6.5 %

Climbing this mountain yourself? Then you can choose between an easy and a difficult side. The easy side starts from Sainte-Marie-de-Campan and is a good training climb with 13 kilometres and 5% gradient. The harder side starts in Arreau and uses only 12 kilometres for the same altitude. That puts you at 6.5% average. However, these climbs are a breeze compared to the other climbs nearby, such as the Tourmalet and the Peyresourde.

Cormet de Roselend

The Cormet de Roselend is more than just a mountain pass; it is a spectacle in the heart of the French Alps, known from the Tour de France. This climb, which has only been part of the Tour 10 times, still deserves special mention for its breathtaking scenery including alpine meadows, a beautiful reservoir, and challenging hairpin turns. With gradients that sometimes exceed 11%, it is not just the climb that tests cyclists, but especially the infamous descent that requires extra attention. It is narrow and has treacherous turns that even experienced cyclists like Johan Bruyneel had trouble with in 1996. He survived a fall into a ravine and finished the stage against all odds. If you want to conquer this col yourself, be especially careful during the descent and enjoy the impressive views and the challenge that the Cormet de Roselend has to offer.

Cormet de Roselend, Beaufort, France

- Distance: 20.1 km, Elevation gain: 1226 m, Average grade: 6.2 %

Col du Tourmalet

The Tourmalet is the mountain most frequently climbed during the Tour de France, no less than 84 times (including arrivals at La Mongie). This pass is an important route through the Pyrenees and is therefore included in the tour route almost every year. If you want to climb this mountain during your cycling holiday, you will therefore encounter a lot of traffic. So you have to be careful on the descents!

Col du Tourmalet, Luz Saint Sauveur, France

- Distance: 18.4 km, Elevation gain: 1385 m, Average grade: 7.6 %

Col de Portet-d'Aspet

The Portet-d'Aspet is not a spectacular climb. Nor is it a regular in the Tour. The main reason for including it in this list is the tragic tour stage in 1995. Italian Fabio Casartelli lost his life here. It has been described out and out. The monument along the route makes you silent. The image of that rider, lifeless on the ground is etched in the memory of many.

It is an easy climb that gets progressively harder as time goes on. The last 3 kilometres of the climb are the toughest with averages above 10%. The climb from Audressein is 18 kilometres at 3.1% average and the climb from Aspet is 14 kilometres long with an average of 4%.

Col de Portet d'Aspet, La Henne-Morte, France

- Distance: 4.5 km, Elevation gain: 433 m, Average grade: 9.6 %

Puy de Dôme

The Puy de Dôme, a volcano near Clermont Ferrand, was the scene of a legendary duel in the 1964 Tour de France between Jacques Anquetil and Raymond Poulidor. Anquetil, a multiple Tour winner, was 56 seconds ahead of Poulidor, his main rival, at the start. On the steep climb to the top, Poulidor rode hard, while Anquetil tactically stayed next to him without making eye contact. In the final kilometre, Poulidor managed to leave Anquetil behind and take a 42-second lead, making the final day exciting. Despite this effort, Anquetil eventually won the Tour with a 55-second lead. On his deathbed, Anquetil compared his fight against cancer to climbing the Puy de Dôme, a reflection on his challenging but influential career.

The Puy-de-Dôme is still only sporadically in the Tour and for the ordinary tourist there is only exceptional opportunity to cycle up. Hiking is possible and so is taking the little train, of course. But the mythical climb will remain a myth for many.

Plateau de Beille

The climb to Plateau de Beille is one of horrors of the Pyrenees. As the name suggests, this is not a mountain peak, but a plateau. It is a cow pasture, populated in winter by skiers. The Tour caravan settles down on the plateau for 24 hours and cycling fans line the flanks with campers and tents for days. In 1998, this mountain was in the Tour for the first time. At less than 30 years old, it is still a relatively new mountain. The finish on this mountain has proved decisive for Tour de France wins on a number of occasions. Both Marco Pantani and Lance Armstrong laid the foundation for their Tour victories here. (although the latter has officially lost that victory)

Plateau de Beille, Les Cabannes, France

- Distance: 15.5 km, Elevation gain: 1208 m, Average grade: 7.7 %

For amateurs, this mountain is a horror. In 16 kilometres you overcome 1255 altimeters, the average gradient comes out to 7.9%. The climb is very even and is continuously above 7%, this leaves little room to recover, only in the last kilometre you can finally gear up and accelerate if you still feel the need.

Col d'Izoard

The Izoard is a true legend; since the start of the Tour de France, this mountain pass has been included in the Tour route 33 times. In the 1950s, duels were fought on the flanks of this mountain that were spread by radio and newspaper. The likes of Fausto Coppi and Louison Bobbet were heroes who were followed and adored from all over Europe. Later, the victors of the Izoard became other great riders such as Merckx, Bahamontes, van Impe and Chiapuchi. At the top of this mountain has never been the finish line, the tour caravan always passing through here. On their way to other places where the heroes finish and are honoured. Their sweat, however, remains forever on the asphalt of the Izoard.

The D902 is the connecting road between Briancon and Guillestre. From these two towns, you can therefore climb this mountain. The north side (from Briancon) is the toughest side to climb, here you can recover the least. The south side (from Guillestre) is a lot longer, but a few kilometres before the summit the road flattens out so you can recover well.

Col de la Croix de Fer

The Croix de Fer is a mountain that has been included in the Tour route a total of 16 times. The first time was in 1947, when Italian Fermo Camellini crossed the summit first. The Croix de Fer (mountain pass of the iron cross) is one of the most beautiful climbs in the Alps. Famous for the fantastic views and the passage along the reservoir. The height of 2067 metres makes m already imposing. It is a mountain pass between the village of Allemont and the town of La Chambre. The Croix de Fer is 2.5 kilometres from the summit of the Glandon. With that, it is often cycled as a combination, just like the Telegraphe and Galibier. So if you do both these mountains in one go, you can easily do so by cycling on for a bit. The Croix de la Fer can be climbed via two sides by bike, as well as indirectly via the north side of the Glandon (from La Chambre). If you want to climb the Croix de Fer from the west side, you start in the village of Allemont. The climb on the east side starts in the village of Saint-Jean-de-Maurienne.

Col de la Croix de Fer, Saint Jean De Maurienne, France

- Distance: 28.6 km, Elevation gain: 1544 m, Average grade: 6.3 %

Port de Balès

Tour de France organisers were looking for new roads in the Pyrenees in 2006. The beaten tracks were well known by now and made for a predictable course. Something new was needed, a surprise for the riders. Through a tip-off, the creator of the Tour de France's route arrived at the Port de Balès. An ideal climb that had never been climbed in a cycling race before. That was no surprise either, as the last five kilometres of the climb were unpaved and almost impassable. No problem for the tour management, who immediately had a number of asphalt roads paved for the riders. So it happened that a new climb could be introduced in the 2007 Tour de France. Since then, it has been a popular col that has been included in the tour schedule four times.

Port de Balès, Bagnères De Luchon, France

- Distance: 18.8 km, Elevation gain: 1068 m, Average grade: 5.7 %

The climb itself is a really tough one. The road is long and and the gradients vary enormously. One moment you are on a short descent, while a few hundred metres further on you find sections of 10%. Here, the secret is to find a good rhythm, but it's not easy. Of course, you can look at it another way. A col with many steep percentages in between which you also have less steep sections to recover completely.

Col du Lautaret

The Lauteret is the easiest way to get from Grenoble to Briancon or vice versa. Going from one town to the other requires crossing a ridge anyway, and the Col de Lauteret is at the lowest point of this ridge. Hence, the Tour de France also regularly chooses this pass during a transition stage to get out of the Alps or as a warm-up for steeper cols deeper in the Alps.

The climb is mostly long from both sides (30+ km) but the gradient percentatges are not too bad. A real runner who just keeps going. So also set yourself up for a long ascent, because after every turn, another long stretch of tarmac awaits! The provincial road is wide, has good tarmac and is generally easy to ride on. Be careful of other traffic, though, as they do not always drive as neatly or take cyclists into account.

Col du Grand-Saint-Bernard

For a one-off outing, we are heading to Switzerland. The Saint Bernhard Pass is the oldest pass in the western part of the Alps. The Romans and Napoleon used this pass centuries ago to conquer new territories. The pass is named after Bernhard of Menton who founded a monastery here in the 11th century, the monks helped embattled travellers who had lost their way in the dangerous area. The famous Saint Bernard dogs were used to track them down. The Saint Bernard Pass connects the Swiss Val d'Entremont with the Italian Valle d'Aosta. The mountain road is only passable from early June to late October; it is closed during the winter period due to heavy snowfall.

The Tour de France has passed over this pass a total of five times, the 2469-metre mountain was last climbed in the 2009 Tour. If you want to climb this climb yourself take your time, as the climb is over 40 kilometres long! There are many Italian motorbikes (especially on weekends) that use the pass as a racetrack, causing many dangerous situations. So it is best to climb this pass during the week. What makes the climb unique is that you have the opportunity to cycle through the famous snow walls.

Col de la Bonette

The Col de la Bonette, with an altitude of 2802 metres, is not only the highest point in the French Alps that can be climbed by bicycle, but also the highest point in the whole of Europe accessible by bicycle. It is known as the highest point ever reached by the Tour de France, with the tour including this col a total of four times. One of the most dramatic moments on the Bonette was during the 2008 Tour, when South African rider Jon-Lee Augustyn reached the summit first. However, on the subsequent descent, he missed a turn and slid dozens of metres down into a ravine. Despite this setback, he climbed back on his bike, but his chances of a stage win were gone. Famous for their tough climb and spectacular scenery, these stages over the Bonette remain a symbol of challenge and perseverance in cycling.

Col du Glandon

The Col du Glandon has been included in the Tour de France route 13 times. Once a Dutchman was first at the top, Steven Rooks was first to pass the summit in the 1988 stage from Morzine to Alpe d'Huez. He also managed to win the stage afterwards. The last time the Tour de France went over the Glandon was in 2013, during a stage that ended at Le Grand-Bornand. Rui Costa managed to win that stage in his name.

The Col du Glandon can be climbed from two sides, namely from Allemond (south side) and Saint-Étienne-de-Cuines (north side). If you climb the east side of the Col de la Croix-de-Fer from Saint-Jean-de-Maurienne, you can reach the top of the Col du Glandon after a short 2.5-kilometre descent on the right. The road over the Glandon was opened in 1898 and is generally only accessible from June to October.

Col du Soulor

The Col du Soulor often forms a pair with the Col d'Aubisque in the Tour de France. The combination of these two climbs, which immediately follow each other, makes a stage extra tough. As a result, stages over the Soulor often become the Queen stage . Only once was there no battleground on the flanks of the Soulor. In 1995, Fabio Casartelli died while descending the Col de Portet-d'Aspet. The following day, the Soulor was climbed in a neutralised fashion. The tour waits for no one, but still respects the participants. With an asterisk dt it did get out of hand the day before. French people gonna be French.

La Ruchère-en-Chartreuse

This climb is not tough, legendary and actually does not even contain a good story. The climb was done once in the 1984 Tour de France. The only fact that makes this climb interesting for this list is that it is the very lowest mountain rated in the outer category. The col is 1407 metres 'low', but was given the extra-low category because the climb was included as an individual climbing time trial. The climbing time trial was won by Laurent Fignon, who laid the foundations for the final victory in Paris here. Unfortunately, this climb is not possible for the ordinary cyclist

Col de l'Iseran

At 2770 m, the Col de l'Iseran is the highest paved mountain pass in the Alps. The Cime de la Bonette, at 2802 metres, is as much as 32 metres higher, but that does not concern a pass. If we are talking about the highest mountain pass the Tour de France can climb, the Col d'Iseran is the ideal bouncer of this list. The Col is named after the area l'Iseran, which in turn is named after the river Isère. That river rises at the bottom of this col in Val-d'Isère. The Tour de France's very first climbing time trial was held on the flanks of the Col d'Iseran in 1939. Starting in Bonneval-sur-Arc and finishing in Bourg-Saint-Maurice, this time trial was won by Belgian Sylvere Maes.

This col is very long, almost 40 kilometres. Just like many other high cols. With amaximum gradient of 8.6%, it averages out to 4.3%. Take note: this col is really high, so in winter it is often closed (and icy).